Future Shock and the Mombasa Roadshow

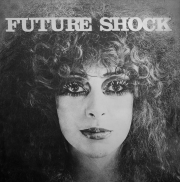

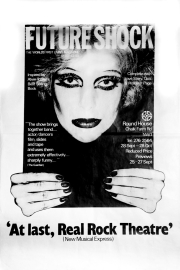

The stories of Future Shock and the Mombasa Roadshow are stories about two very different Theatre experiences and deserve to be told. They are linked by one particular person, Mary East. It is her extraordinary image that appeared on all the publicity, and the Album cover, for the production of Future Shock. She later went on to be a founder member of the Mombasa Roadshow. Before I talk about her, I want to go back to how I became involved in both companies, starting with Future Shock.

FUTURE SHOCK

After the collapse of the rehearsal’s for ‘Amedee, or How to Get Rid of It’ by Eugene Ionesco, [ See the story of ‘The Lion of Eaton Square’ ] I went into a bit of a meltdown. 5 month’s of intensive rehearsal’s during the sweltering heat of the Summer of 1976, all came to nothing after the departure of one of the cast…without explanation! It was my first foray into a kind of theatre that Drama School hadn’t prepared any of us for but it was exactly the kind of theatre I wanted to be part of. It was the very definition of experimental and I wanted it to be my future. After a very conventional start to my life in the theatre, followed by 3 years at The Central School of Speech and Drama, I was ready to pursue what I had always dreamed of doing and start to approach theatre in the same way that rock band’s approached their formation and their music…with a blank sheet. But my first lesson had shown me that this was a very different world where you wrote your own rules and, on the whole, had to be prepared to work very hard, often without pay or financial support. For the first time in my life I was truly excited about the possibilities of what might lie ahead.

But that didn’t last long. Over the following few weeks, I struggled to come to terms with what had happened in Eton Sq and I lost myself in a life of sex and drugs and rock’n’roll. None of which helped me to understand where or what I was going to do next. I was too reliant on things happening by chance rather than by design. It was a lazy way of approaching life and meant that if chance didn’t throw up new opportunities, I was all at sea and adrift both emotionally and psychologically. Then, towards the end of October, chance did throw something at me but it wasn’t what I particularly wanted or expected.

Whilst at Central, I had met the daughter of the wardrobe mistress. She was a theatre producer and happened to live with the Road Manager for the Rolling Stones. In the last week of October, I received a phone call from her, she said she had a job for me. It was her mother that had suggested me and because of her interesting connections, I got quite excited. Sadly, the job she offered me was as an Acting/ASM/Understudy in a production of ‘The Ghost Train’ at the Old Vic. Not what I had anticipated and not what I really wanted but I was desperate for work and I thought, at least it would be something that I could invite my parents to after their concerns about what I had been doing in Eton Sq. It seemed that I couldn’t escape my dual life of conventional theatre versus experimental theatre but at least, working at the Old Vic on an up-market production couldn’t do me any harm and it was relatively well paid too. The star of the production was Wilfred Bramble of ‘Steptoe and Son’ fame and I certainly earned my money. I had a one line part as a policeman but the real work involved having to learn three other roles in the play. I understudied, James Villiers, Paddy Newell and Geoffrey Davies. Physically they couldn’t have been more opposed in height and girth…and I had to go on for all three during the run of the show and in their costumes. It was a nightmare. I also had to help with the special effects which the playwright, Arnold Ridley of ‘Dads Army’ fame, had specified to the last inch. It involved running a large garden roller over wooden slats across the full width of the backstage area, to replicate a train running through the station, plus other sound effects. One of my abiding memories of the production, apart from having to give very mediocre performances in very ill-fitting costumes at a moments notice and virtually without rehearsal time, was that Wilfred Bramble had a habit of coming in to the theatre very early and sitting in his dressing room drinking, what I believe was gin and water, in a large glass. This meant that on his final exit through the ticket office window at the end of the production, he was so drunk that he collapsed into my arms and had to be virtually carried back stage, where I had to ready him for the curtain call. Who said theatre and working with stars was glamorous? In many ways it was an object lesson in why you shouldn’t work in theatre. I also realised that, as Wilfred Bramble had played Ringo Stars ‘Uncle’ in the Beatles film of ‘A Hard Days Night’, I was beginning to have a career as someone who worked with people that had also worked with the Beatles [ see ‘Dick Wittington and other Stories’ ] but without the glamour of actually working with the Beatles themselves. When the production transferred to the Vaudeville Theatre and then flopped, I was mightily relieved.

At the time, I was sharing a flat with my old friend Andy Ward, who was the drummer with the very successful band Camel and so it was very easy for me to slip back into the world of sex and drugs and rock’n’roll again. I was ‘seeing’ three different women at the time and although that may have sounded glamorous, it was also draining and very unfocused. I didn’t know what I was doing half the time but it helped to distract me from the absence of work. I was 26yrs old and apparently, living the life that many people of that generation wanted to live. But something wasn’t right. The more drugs I took to dampen the emotional rollercoaster I was on, the worse things became. Around 1973 I had been diagnosed as having clinical depression and was offered a smorgasbord of anti-depressant’s by my doctor but mostly they just seemed to amplify my problems and one by one I rejected them. So I ‘self medicated’. Andy was on an even more extreme rollercoaster than me and his success gave him the money to douse his psychological problems with more drugs and more alcohol than I could afford, but for a brief period in time, we seemed to be heading in the same direction…oblivion.

I’ve just re-read my diary for March 1977 and it’s a scary document where I’d recorded my daily frame of mind and it doesn’t make for comfortable reading. As with many people working in the performing arts or any creative medium for that matter, I needed a creative anchor to channel all this energy…some pegs to hold my tent down before the next gust of wind blew it and me away. And then, on March 24th, I managed to identify three productions that were holding auditions over the following three days. All of which sounded really interesting and all of which were for leading roles. So I made three phone calls and was invited to attend all three. This was rare indeed. The first was for an experimental theatre company in Germany, who were going to be based in a castle in Heidelberg and had substantial funding behind them. I was required to do some recording for the audition and after being interviewed over the phone, I was offered a leading role. They were a bit surprised when I said that I couldn’t commit to it until the following week because I had two other auditions that weekend that I had to attend first. The second audition was at the Hampstead Theatre which was just down the road from Central, my old college. It had a very high status reputation as a production house with strong links to the West End and the National Theatre. All I can remember was that having been offered the job in Germany I was free of anxiety about having to get this job and I went into the theatre with a level of confidence I’d rarely experienced before. Neither of these auditions had required prepared pieces, which were my bete noire, and all I had to do was turn up and do a reading. For the second time in two day’s, I went home and later, received a call offering me the lead role. Again, I astounded them and myself by saying that I would have to let them know in a couple of days because I had another offer on the table and I needed to think about it. This wasn’t normal. This was already an astounding position to be in and I still had a third audition to attend on the following Monday. This particular audition was advertised in Time Out, which wasn’t considered a place for serious theatre to be advertising in. It mentioned that it was for a piece of ‘Rock Theatre’ and that wasn’t a term that was in common parlance at the time and there was something about it that chimed with me. In many way’s this was the audition that had intrigued me the most and was why I hadn’t leaped at either of the first two offers. If this really was a piece of Rock Theatre, this was what I wanted to do. This was what I’d dreamed of and there was something else about this audition that excited me, it was to be held at the Roundhouse. I loved the Roundhouse and yet another attraction was that my sister had worked there for a while as an accountant. It felt like family. What I didn’t know, was that I had the part on offer before I even set foot in the place. I later discovered that when I rang to say I was interested in attending the audition, the woman who answered the phone, Fay Chung, had turned to her partner John, the writer of the piece they were auditioning for and said “At last we’ve found him”. Just from my voice and the way I spoke about my interest in this, as yet, untested form of theatre. John, was John Saxby, and he had been preparing for this production for two years whilst working as a sound engineer at the Roundhouse. He had been looking for exactly the right people to work with for just as long. The piece was called Future Shock!

When I arrived at the Roundhouse on Monday 28th, the woman working at the Box Office said that John was in the building and that I should go through. I’d only ever been there as a member of the public, for the infamous Sunday Rock Concerts, so I wasn’t quite prepared for the vast space and the quietness of it when empty. John, Fay and an extraordinary looking woman were sat talking when I entered and I walked over and introduced myself. John had shoulder length hair and looked like the archetypal rock star hippy type. Remember, I wasn’t aware of the circumstances behind the phone call I’d made before and so I had no idea how the audition would be conducted. They asked me to sit with them and John proceeded to tell me about the show and about my role in it. I’d be lying if I were to try and tell you what was said over the following period of time but I got an immediate sense that I was auditioning them as much as they me. I know I felt very relaxed and that it was an enjoyable meeting and that I loved everything they were telling me about the concept for the show. I can’t even remember at what point they told me that if I wanted to be a part of this adventure, the part was mine, but it seemed to be implicit. The character they were casting was called Roger and he was an ‘everyman’, not a particularly exciting role and not very well written. If I were to accept the role I would be instrumental in fleshing him out and even re-writing his dialogue. He explained that there was a cast of four and that he and Mary, the woman with the extraordinary hair and make-up sitting with them, were ‘Media’ types and that I and a woman, yet to be cast, were representative of your average man and woman on the street. It was to be a living magazine, with articles about fashion, art, religion and the latest medical advances in family planning, for instance. It was also a love story, set over an unspecified period of time. There would be a rock band centre stage that they had already recruited and the music had been written by him and his friend Lionel Gibson. Depending on finances, there would be screens with live and recorded action happening throughout the show. Was I interested? Oh yes, I was more than interested. I explained about my extraordinary few days and that I would need to make some phone calls and say no to the other two company’s but I was definitely in. He then explained that there was a downside to all of this and that was that they had hardly any money and initially there would be no pay and that they were still trying to get a venue/theatre in which to put it on. Did that bother me? No, was my unequivocal answer. He also explained that they would be casting the woman’s role on the following Saturday and that the choice of who I would be performing with would be mine. They believed in organic casting and it made sense that I should make that decision for myself. And lastly, would I like to come to dinner on Thursday evening and hear the music and read the script? My family and more surprisingly, my friends, were aghast at the choice I had made but it wouldn’t be long before that choice would be vindicated.

I walked out of that building and floated back home, on air. I don’t think I’d ever felt that way before, or since. All I knew was that I’d probably just made the most important decision of my life. There was a brief hiatus over the next four days and then the pace started to pick up. On Saturday, John, Fay, Mary and I assembled at the Roundhouse for the final audition. The female characters name was Rowena and John had invited a number of actresses to attend. I hated auditions and had strong feelings about the whole process. I felt that most Actors were at their worst during auditions, I certainly was, and that as an auditioner there was something far more important to pay attention to and that was, a feeling. I maintained that you often knew who was right for a part within the first couple of seconds of someone entering the room. It wasn’t about their ability to recite a much rehearsed piece of text but about their ability to take direction and to adapt when asked to try something different. More than that though was a feeling about whether you wanted to work with them…or not. As the first couple of auditionee’s came and went, we were all in agreement that they weren’t right and then the next actress came in and I got an instant sense that this was the one. She was full of life and was self deprecating in a nice way. She’d never acted before but had a background in dance, of a commercial kind. Panto, Summer Seasons etc. There were a few dance pieces in the show so that immediately ticked an important box. She had a soft midlands accent and she was just natural and fun to talk to. She fitted. The final clincher was that her name was Pamela Wendy. The other’s didn’t know this but my mothers name was Pam and my sisters name was, Wendy. If this was organic casting, she had the part just on that basis alone. We were very professional and thanked her and asked her to wait outside as we needed to make a choice today but still had others to see. As she left the room, I turned to the others and said “She’s the one” and then I told them about the name connection. I think they had had the same gut response to her that I’d had and we could barely contain our excitement. We saw the remaining contenders but none of us was in any doubt that Pamela Wendy was exactly the person we were looking for. When we called her back in, she was completely blown away that we wanted to work with her. She had taken one look at the assembled company and had just assumed that we were looking for someone more like us. Leftfield or alternative. John filled her in on the what’s, when’s, and how’s and her excitement was palpable. John had told us before the audition that he’d finally done a deal on a venue and that we should be prepared to leave for Newcastle within the next few days. We all returned to our respective homes to prepare for the future…and Future Shock.

It was beginning to become apparent that John was a deal maker, the like of which I’d never met before. He’d been in discussions with the Minister for the Arts over the Newcastle University Theatre. It had been ‘Dark’ for some months due to a lack of Arts Council funding and John had persuaded him, with obvious logic, that whilst ‘Dark’ it was a wasted utility. If the Minister were to allow John to take it over for a couple of months, rent free, John would guarantee to fill it and make money for both parties. The Minister agreed. The theatre came with a Stage Manager and Front of House staff. They were all on furlough [a word that has taken on considerable importance during the Coronavirus Pandemic] and were therefor costing the Arts Council money, without returns. It was a win win situation. John was supremely confident about his ability to fill the theatre and fulfil the Arts Ministers expectations. Extraordinary. I’d love to have been a fly on the wall during those negotiations. I’ve often wondered if the Minister also understood that a crucial part of the equation was that we all needed to be claiming benefits for us to survive during the rehearsal period. John’s confidence in himself, in Future Shock and the fact that it was going to make money, was without parallel. His self belief was infectious.

I think I should say something about the book that inspired John to write, or construct, this performance piece. The book was written by the ‘Futurist’, Alvin Toffler. It was published in 1970 and has sold over 6 million copies and has been read by half as many again. It was and is a phenomenon and continues to be a hugely influential book. It’s basic premise is quite simple to grasp and the book just repeats that basic premise over and over again showing how it’s effect’s are felt by every person on the planet. And that premise is that as the cutting edge in any area advances, it leaves in it’s wake, victims of Future Shock. Take fashion for example. If you grew up in the 50’s and you were a Teddy Boy, you were, at the time, on the cutting edge of fashion and anyone still wearing their de-mob suits was a victim of Future Shock because they were now behind the times and that example extends into the next few decades. Mod’s, Rocker’s, Hippies, New Romantic’s and so on. A more contemporary take would be phone technology. If you think you’re on the cutting edge because you’ve just bought Apples latest Smart phone, two weeks later you could find that someone else has bought out a phone that has some facility that the Apple phone didn’t have and you would have just become a victim of Future Shock because you are now behind the curve in phone technology. As the speed of change accelerates, we are all increasingly becoming victims of Future Shock and most of us just stop trying to keep up with the latest thing and therefor become lodged in the past… exhausted by the need or desire to keep up. I’m a classic example. I do possess a smart phone but I don’t use it because I hate them. I hate walking down a street and seeing almost everyone on that street staring at their ‘devices’ and being completely unaware of what’s going on around them. In my view they might just as well have stayed at home and gone out ‘virtually’ instead. They have become slaves to the internet. However, it is me that has become the one that is out of step because, like it or not, that is the future and I’m the one stuck in the past. I struggle to have conversations with the younger generation about literature or culture because one of the effects of Future Shock is that people have shorter attention spans and can’t be bothered to watch a whole TV programme or read a whole book, because it takes too long and they just want bite sized chunks of information instead. Why does any of this matter? Well, because it can engender fear of being left behind. It can isolate people. And not just individuals but whole Nations and Cultures too. It can and does disadvantage anyone that’s not keeping up and it can and does effect peoples attempts to gain employment for example. It effects everything and everyone. Art is another obvious example. I went to David Hockney’s exhibition at the Tate a few years ago and in one gallery there were iPads hanging on the wall and you could watch work being created in real time. I loved it and I love a lot of Installation Art, I’m probably close to being with the cutting edge there and with music too but more generally, I’m the perfect example of a Future Shock victim. Interestingly, the examples that John chose to highlight these ideas with, weren’t specifically from the book and that fact became pertinent later on during the development of the show.

The next few weeks found us, with Johns now familiar confidence and our growing confidence, doing TV, radio and newspaper interviews. I don’t think the irony of how we were publicising a show that none of us had actually seen, in it’s entirety, was lost on any of us. We had all become, to quote the title of one of the numbers in the show, ‘Temporary True Believers’… which was Johns take on Religion. But there was a flipside to our growing public profile…we were all poverty stricken. Living in very rundown properties and subsisting on Social Security. This could and did make our lives quite difficult. And there was another downside which also became more and more evident as the show progressed, John was so busy ‘taking care of business’ that Mary often had to rehearse by herself, making her feel quite isolated and Pam and I had to rehearse without direction. Pam taught me to dance and I tried to help her with her acting. For Pam and me, this was a double edged sword. I think we brought an awful lot to the pieces we were involved in [virtually everything] but there was no sense of an overall picture and Johns perpetual absence was increasingly problematical, especially for Mary. But we ploughed on and fortunately for John and the show, we were a very hard working group of people who retained an absolute belief that we were working on something very special and potentially groundbreaking. The band that John and Lionel had recruited to be at the centre of the show were a bunch of local lads called Cirkus. They were used to making a decent living, performing covers of other peoples material. They had wives and children and had taken an enormous gamble to come on board. But they were brilliant and although they struggled with the whole concept of being a part of somebody else’s show and also having the distraction of sharing a stage with actors, they were really hard workers and very professional. They also brought a fan base with them and I’m not sure how much we appreciated that at the time. The Stage Manager and all the people that became part of our extended family, were all instrumental in getting us across the winning line and by the time it came to opening night, it felt like the whole of Newcastle was willing us forward. It was an incredible feeling.

As with the retelling of any story, especially one that took place 43yrs ago, there are many details that now allude me so, without collaboration, I’m telling this from my point of view alone. I’ve recently been in touch with Mary East and we’ve talked about feelings rather than specifics, but I will stand corrected if when she reads this I’ve misinterpreted what I think happened. Pam and I had started to have a relationship during the rehearsal period and so a blurring of fantasy and reality had set in. The company saw this as grist to the mill and felt it added a certain frisson to events and added to their belief in our on-stage relationship. I just felt awkward, especially as Pam was married. This can happen when you’re in a bubble. It’s not healthy but if you approach your acting from the ‘method’ way of working, it’s easy to get confused between reality and fiction. The first preview was canceled because we had done an interview with the BBC and it was going to be broadcast that same evening. John decided that it would help put bums on seats if we delayed by one day…and he was right. I believe that first night was almost sold out.

At this point I think I need to say that I’ve been trying to find John and Fay for some time now, in anticipation of writing this piece but Mary, who I’ve only just managed to track down in the last few weeks, told me that John passed away just before Christmas ’19. I really wanted his blessing and help with this story because there are so many details that only he could help me with and now I can only second guess some of that detail. I’m so saddened by his death and furious with myself for not doing this sooner but I wasn’t ready before now. Anyway, that first night went pretty well as I remember it. The audience were always going to play a large part in the show, as with any performance, but especially with this show because I, as Roger, addressed the audience directly to draw them into his story. John walked amongst the audience at one point and asked them questions and until we saw how they responded to us, we had no idea if it would work or not. It was a crucial element of the show and I remember both John and I being delighted by the audiences reaction to us and that, in itself, told us we were on to a winner and gave us the confidence to build on those connections. I think John was especially surprised at the number of laughs he got and I was delighted when the audience became emotionally involved in my story and so I started to develop that over the coming weeks. We seemed to have a winning formula on our hands. Part rock concert, part love story and a touch of pantomime. There was also an intellectual subplot that questioned peoples understanding of human nature and where the future lay. The music was good, memorable and played at the sort of volume one would expect at a rock concert. This show had everything. I can still remember the buzz at the interval as the audience left the auditorium. This was special. This show had legs. Even my rather conventional parents who had driven up from Surrey to see it and who had never heard amplified Rock music before and who I fully expected to find too much… absolutely loved it. So, not just legs but cross generational appeal as well. This was so much more than we could possibly have hoped for.

Over the next few weeks we got better and better as we refined our performances…and the audiences just kept coming. I’m not exactly sure when Alvin and Heidi Toffler and their daughter Karen first showed up from America but when they did, they seemed to become instant fans. They were really friendly and easy to be around but to this day I have no idea what John had agreed with Alvin regarding the use of the name Future Shock. This is where I needed Johns input because I was never sure what Johns relationship with Alvin was. I just assumed that there was no financial arrangement because John kept things like that to himself and at this stage there wasn’t much money to talk about. I also don’t know what John had agreed with the Theatre or the Arts Council or the Band. What I did know was that we, the cast, were payed next to nothing at this stage. This was no cooperative. In fact our whole relationship with John was one of trust. What I can say is that John had a touch of the Richard Branson about him and I can only assume that he always had his eyes on a bigger picture. He was a very ambitious person…but a very ambitious person who dressed like a Hippy and talked like a Hippy but a Hippy who didn’t take drugs and wasn’t necessarily into Peace and Love.

The obvious question after such a successful first outing was, what next? John had always talked about how he really wanted the show to look and develop and it was this vision, in part, that we had all bought into. Newcastle had been a very good ‘Fringe’ production and had served it’s purpose as a testing ground but what needed to happen to take it to the next level, would involve a lot of money, and the technology of the sort that John envisaged using would not come cheap. But we were about to be given a second bite of the cherry. The producer of the BBC’s Nationwide programme in Newcastle had become completely enamoured of the show and, like so many of us, had fallen under John’s spell of a bigger vision. He had somehow managed to get us a prime venue, the YMCA, at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival, 3 months away. I don’t think it was ever intended to be any more than we had done in Newcastle, there wasn’t enough time or money for big changes but it was an opportunity to open it up to a much wider audience and would give John more time to find backers for something much more ambitious…and he seemed to want to keep the same team and cast. We were all very keen to stay for the ride.

For the next 3 months I worked as a delivery driver for a bakery in Hampstead. These moments of Hero to Zero are well known to most actors and are very grounding. This time however, I had the luxury of knowing that after the 5am starts of doing this very unglamorous job, I would be going back to starring in a wonderful show in one of the most beautiful city’s in the world. John had arranged for us to go back to Newcastle to rehearse for Edinburgh. By this time Pam and I had ended our relationship but we were still a very good team and I think Mary had started to realise just how crucial she was to the show and was far more relaxed about her role. We all were. After a week in Newcastle we then had another week in Edinburgh to get things up to speed and for John to, yet again, do his amazing publicity rounds.

I have to confess to something of a master stroke on my part regards publicity. We were already creating a bit of a buzz, which isn’t easy at the Edinburgh Fringe, so the organisers offered us a truck for the opening procession. We had a meeting to try and decide what we should do with our truck. Most company’s take this opportunity to blast the audiences along Princess Street with amplified music or extravagant ‘acting out’. It’s a real battle to get noticed, especially when you consider that the truck’s are moving and the audience only have a couple of minutes at most to assess what’s on offer. We were getting nowhere with anything beyond the usual suggestions and then I suggested that we should send an empty truck down the cavalcade. No music, no acting…nothing. Just two posters on the truck doors. I argued that it would baffle the assembled public and create an almost funereal atmosphere and potentially cause a bit of a stir…and boy did it. It drew everybody’s attention. Amidst all the cacophony and madness there was a stunned silence as this empty, silent truck went past with just the words Future Shock visible, and I think Mary was sat in the passenger seat. I had to fight for this idea with the company and the organisers and other theatre company’s weren’t too pleased about it either but eventually we got the go ahead. Either way, our first night was sold out.

For an unknown company with an unknown show, it was a real coup. And because the show also came up with the goods, we sold out every night. We were one of THE shows to see that year and people queued for returns. John had even done a live recording of the show and produced an Album [of dreadful quality if I’m honest]. It had a small production run and didn’t sell that many copies but because of that it now has a considerable rarity value. One of my favourite tales about our time in Edinburgh was that one evening after the show, there was a letter waiting for us addressed to the company. It was from Dame Janet Baker, the Opera singer. She was performing up the road in the main Festival. I’m not a fan of Opera but found it extraordinary that someone of her stature and from the classical world would have come to a show like ours…but she had, and loved it. The letter invited us to go and have tea with her the next day at the theatre she was appearing at. I went and I think it was Pam who joined me but two of us did go and upon arrival were ushered into the stalls whilst she was doing a warm-up on stage. She saw us arrive and directed her singing to us and after about ten minutes stopped and came down to where we were sitting and asked us back to her dressing room for tea. She was completely charming and just wanted to talk about our show and about Alvin Toffler’s book. She had read it and thought we had perfectly captured the spirit of it. She said it was one of the most exciting things she’d ever seen in a theatre. It’s a real shame that the others didn’t come. Why wouldn’t you accept such an invitation?

A few years later, I was in Australia and the day I arrived, Dame Joan Sutherland was giving a free concert in the botanical gardens in Sydney. For some reason, in the intervening years, I had confused these two great singers and I thought, by then, that it was Joan Sutherland that I had met in Edinburgh. The people I was staying with were going and so I went with them. When I told them about Edinburgh, they wanted me to go backstage afterwards and get us invited in to meet her. She was an Australian icon and an invitation to meet her would have been very special to them but I declined and said I couldn’t do it, which is just as well as it turned out. Imagine the embarrassment if I had gone backstage and Joan Sutherland had, quite rightly, claimed never to have met me. Anyway, for reason’s far too complicated to go into here, I felt that I would only have had a sad story to tell. When I thought I had first met her, it felt like we were on level ground. After all, for that brief moment in time, I thought she had been our fan and here I was in Australia a few years later and my circumstances had done a complete flip since I thought we had first met. I was there with a truckload of unhappiness and was running away from life and myself… in the depths of depression. I didn’t want to meet me, why would she want to? Fortunately that never happened and so all awkwardness and confusion were averted. I apologise to both these great singers for getting them mixed up.

So, I’ve burst the bubble now. This isn’t a story with a happy ending, in case you hadn’t already guessed that. If it had had a happy ending, you would probably know who I am but you don’t. At the point we were at, it was a wonderful story and it was unimaginable that it could go anywhere but up. After I returned to London, the realities of life kicked in again and I managed to get a job driving for a company called Audio Video. As driving jobs go, it was a good one. I even spent a day with Twiggy, helping her in the office and an afternoon with the film director Lyndsay Anderson and then a couple of weeks in Cannes at the MIP Festival. From time to time we did Future Shock related stuff and John insisted that it was just a matter of time before the next chapter unfolded. He was already recording a new, better album, at De Lane Lea Studios in Wembley. I was going to voice coaching classes, paid for by John and even spent a day at the studios to record the one number I sang on and Mary also did a bit of recording. I remember her coming into the production suite to tell us that she had just been to the Ladies and in the cubicle next to her, she’d heard Siouxie Sioux of The Banshees practising her vocals. It felt like things were moving forwards and bit by bit John told us about deals he was beginning to do. For instance, Tony Palmer the film director had drawn up a contract with John to make a film based on the stage show…with the original cast! And then there was a contract to make a TV series with ITV/Granada. It also emerged that The Drury Lane Theatre in Covent Garden was being kept dark in anticipation of our transfer there.

This was both exciting and terrifying at the same time. I know that Mary and I were completely ambivalent about achieving fame and the sort of money being talked about that would have turned us into millionaires overnight. This was becoming so real, you could taste it and trying to take on board how our lives were about to change was effecting us profoundly…and not always in a good way. I’d seen first hand what fame could do to people. My friend Andy Ward had become pretty famous with Camel and it didn’t always sit well with him and at college I had got to know Carrie Fisher slightly and that was before Star Wars was released. With her mother being Debbie Reynolds and having Cary Grant and Elizabeth Taylor as God Parents, she was born into Hollywood royalty and that alone had messed her up. Amazing as it was to be involved in a project that appeared to be so universally admired, there was also a sense that any artistic input, let alone control, that we had had up to this point would surely start to slip away from us in a fog of money and contracts and corporate interests. Mary and I weren’t naive and we knew that, as we’d never signed any contracts with John, his words had become hollow because our involvement in Future Shock’s future was by no means certain. And so we waited. Our lives on hold whilst we did our mundane jobs to try and keep body and soul together. Then, out of nowhere, into this extraordinarily pregnant air of expectation, a bomb fell. [ See postscript at the end of this story ].

For reasons which I still find incomprehensible, especially with regard to our show, Alvin Toffler’s lawyers had decided that the name Future Shock was a ‘brand’ and that if we wanted to continue to use it, we must pay. The reason for this was that, in America, people had started to use it as a descriptive noun. Most noticeably in the ‘Judge Dread’ comic’s which referred to some characters as ‘Future Shockers’…it had entered the lexicon and they felt it was time to cash in on this. Our show had little to do with the book itself but the fact that we were using the ‘brand’ name, was enough. They wanted a slice of the action and they wanted a substantial slice. Overnight, we were dead in the water. One by one, all interested parties dropped out. The irony of this ‘Branding’ exercise was that Alvin Toffler himself had ‘borrowed’ the term from some other scientist’s but at the time they didn’t seem to mind. They were reportedly just flattered and allowed him to use it as the title for his book. What I find so difficult to understand is why Alvin, who was a big fan and supporter of the show, hadn’t discussed this with John. I can only speculate. Perhaps, up until now, we had just been a bunch of artist’s with this great little show…the emphasis being on ‘little’. Suddenly, big corporations were showing interest and big money was about to be involved. This was greed, pure and simple. Alvin was a multi millionaire, he didn’t need the money. Why on earth did he allow his lawyers to do this? Especially to us? I’ll never know. As I said previously, John died just before I started to write this story and I now know that Alvin Toffler died in 2016, his wife Heidi died in 2019 and their only child, Karen, died in 2000 from Guillain-Barre Syndrome.

I’ve never felt seduced by the notion of fame, I would hate to lose my privacy. Money has also been low on my list of priorities but I’m only human and when somebody wants to reward you for the work that you do, it feels good. The situation had felt so real and so imminent that I had allowed myself to think the unthinkable…what would I do with all this new found wealth? Roger, the character I had played, wasn’t a particularly challenging role. He was everyman, he needed to be bland, an empty vessel. He’s pulled and pushed, this way and that by a media that tells him how to dress, what music to listen to, what sort of relationships he should be having. What car, what art, which holiday etc, etc. But leaves him dangling when his bank account runs dry or he becomes unemployed. Relentless when functioning but heartless when thing’s go wrong. What would I, Chris Morton do? Rather spookily, as with so many aspects of this show, life had taken on a reality rather too close to the shows story line. My relationship with Pam had broken down, as in the show’s story line, and the media and artistic community had dropped us like bricks. We too felt hung out to dry. The beast was dead.

Over the course of the following year however, it became apparent that John had not given up on it quite yet. He was looking for another backer. How this would work with Alvin’s lawyers, I had no idea and yet again, I could only speculate. Again, John kept us in the dark regarding his relationship with Mr Toffler. John indicated that if we could come up with between £10-£20 K, it could still be done and he hinted that The Roundhouse might be a possible venue. So, Future Shock was not drowning, just waving. I was initially kept very distracted with a busy driving job, as I’ve mentioned above and a hectic love life…again. But the three women that I was involved with, all of whom had names that when spoken could be men’s names [go figure Mr Freud], culminated in me meeting and falling in love with the love of my life…but that’s another story entirely. Back to the plot. Again, the story of Future Shock was never a conventional story and the next chapter fits that pattern. I happened to be visiting a man in SW London to purchase some exceptional Hash. Nepalese Temple Balls if you must know. And if you do know, you know that Hash doesn’t come any better. I digress. He was an unconventional person to be buying Hash from, in the sense that he worked in the City. He was a financial advisor and dabbled in Cocaine but had been offered a substantial amount of this Hash and had no personal interest in it’s consumption. We started to chat and in the course of our conversation I told him the tale of Future Shock and his eyes lit up. He had recently been told by a colleague of his that he had been instructed by four of his client’s to look for a ‘different’ and possibly ‘artistic’ project, to invest a relatively small amount of money in, as a punt. “How much is small” I asked. “£3,000 each” came the reply. I couldn’t quite believe what I was hearing. I immediately took his colleagues phone number and asked if it would be alright if John were to call him because I felt that we probably had the perfect investment for them. And so it turned out to be. I wasn’t involved in the negotiations but very quickly, John had the money in place and then in yet another twist, one of the investors decided that he was going to buy the other three investors out because he wanted to be the sole investor. His name was Peter de Savary. I should point out that at no point was Mr de Savary in any way aware of the line of connections leading up to his involvement in our show. He had immediately fallen under the spell of Future Shock, as had so many before him. We were back in business!

This third outing for Future Shock had a very different feel to it. The thrill of presenting it for the first time and feeling we had something new and special to offer to a town that had taken us into their hearts before we even opened, could not be replicated in London. Edinburgh was us showing off with the confidence of Newcastle still ringing in our ears. But London was the epicentre of not just the UK but arguably the world when it came to theatre. This time the promise of something new, something the like of which had never been seen before, really had to be backed up. London can be a very cynical place. It’s where the chaff get’s sifted from the corn and the critic’s sit back in their seat’s and say, “So what have you got that’s so special?”.

For the first time I started to feel that the absence of a director was a real problem. We were beginning to get bogged down with learning to use and adapt to all the new technology. Radio mikes instead of stand mikes. John and Mary now entered and exited on hydraulic lifts. The band where daunted by the reputations of all who had gone before them, especially at the Roundhouse. The multi media that we had used before was distinctly amateurish. We now had a screen that opened up in the middle of the stage showing live and recorded action and the cyclorama that had previously had slides projected onto it was now going to have animations that started with the actors, me and Pam, going into a freeze and them taking over on the screen and ending with us taking over where they left off. The effect would be stunning. And crucially, it all had to work like clockwork. If it was delayed or didn’t happen we would be left with some serious egg on our faces.

Right from the outset, things kept going wrong and crucially, there was no sign of the animations. This meant that rehearsals where disjointed and missing crucial elements that we needed as performers so that we could time things correctly. The radio mikes didn’t always work so that Pam and I would find ourselves suddenly having to project acoustically when we should have been able to do our dialogue subtly and when you are acting against a backdrop of loud rock music, that simply didn’t work. We looked and sounded ridiculous. The hydraulic lifts were also unreliable, undermining John and Mary’s confidence. All our rehearsal time was being taken up with technicians desperately trying to fix things and the cast sitting around with an increasing lack of confidence in the technology but more crucially, in ourselves. And one of my repeated pleas to John was. “Where are the animations?”. He seemed to be unaware that for Pam and I, it was like rehearsing with crucial members of the cast absent.

This state of affairs continued right up until the first previews were just a matter of days away and the atmosphere had become poisonous. I was beginning to be seen as negative by John because I was increasingly questioning the whole viability of the show without some of the most important elements being in place. It all came to a head when it was ‘discovered’ that the man responsible for the animations simply hadn’t done them…they didn’t exist! I still struggle to understand how John could have allowed this to happen. We had also started to go way over budget and although Peter de Savary’s pockets may have appeared deep, we were now inching towards a spend of over £60-70,000 and with other problem’s arising almost every day. It was decided that one element that needed serious first aid could be resolved, but it would cost upwards of £10,000. Lighting. We needed someone to come in and perform magic with the lighting, in the hope that it would distract from the gaping hole in the animations. One of theatre lands best lighting men was brought in to cast his magic wand over the whole production…in a matter of day’s. Which he did. But even he couldn’t hide the lack of action on the large cycloramic screen that ran across the the back of the whole stage.

The previews were postponed and that never bodes well in the eyes of the awaiting critics and public. By the opening night we had to summon all our reserves of professionalism to walk out on that stage and perform. We were still having problems with the radio mikes and I can remember the humiliation of trying to act acoustically and on one occasion walking over to one of the bands stand mikes to deliver some dialogue, just so that I could be heard. Over the coming day’s most of the technical problems were ironed out but it was too late, the judgement on Future Shock had been made and not unsurprisingly, it had been found wanting. It was a disaster. My last memory at the Roundhouse was walking down a staircase with Peter de Savary and me apologising for letting him down. He was very magnanimous about it all and just said that, as a racehorse owner, he had had to make some very difficult decisions about injured horses and some of equal value to the loss he’d made on the show [£80,000 ]. “C’est la vie”. I should add that I am not a fan of horse racing and it’s consequences for many of the horses but having been around that particular ‘Industry’ all my life, I could see where he was coming from. He said he’d really enjoyed the ride [No pun intended].

We continued the run at the Roundhouse but with the knowledge that this was probably the end of the road for Future Shock. We had quite good houses and we put on a good show but it was a pale shadow of what had been promised and what we had wanted it to be. The band had to return to Newcastle to pick up from where they’d left off. They had families to support and a fan base to get back to. In many way’s they’d made the biggest sacrifice of all and we all felt sorry for them. The rest of us just had to pick up the pieces and look for work. After 2yrs of our lives thinking and dreaming about Future Shock, it was over. I consider myself particularly fortunate because a few weeks later, I received a call from Neil Cooper, the Production Manager at the Roundhouse, offering me a job on his team. Just a bit of part-time work to begin with and then full time from the following February. He wanted me to act as a bridge between the regular Roundhouse crew and the Manchester Royal Exchange Theatre Company who were embarking on a season there whilst their base in Manchester was being re-furbished. And before that there was the Rustaveli Theatre Company of Georgia doing Richard III. Probably the single most important and best piece of theatre I’ve ever seen. Some years later, I called Neil to ask him what my job title was whilst working with him. I had always thought I was just a humble team member. I was putting a CV together and needed to know. “You were my Deputy Production Manager” he replied. “Really?” was my response. I felt enormously flattered and quite emotional. I had loved every minute of my time working with Neil and the team and it more than compensated for the abject failure of Future Shock. That just felt like the icing on the cake. Me, a Deputy Production Manager, who’d have thought it. And I was in love…really in love.

I never saw John again. I had always wanted to talk to him but perhaps the conversation I wanted to have would have been too difficult for him. I had imagined a very different version with even more cutting edge technology and far more cutting edge electronic music and regular, up to date, media insert’s, on a daily basis. A true living magazine. With me directing and possibly minimal live action, mostly audio/visually based. I still think that that could have worked, even now. It was a great concept that could have constantly changed with the times and run and run and run. But lets stop there, none of that ever happened.

The only person I kept in touch with was Mary but it would be a few years before we collaborated again and in many way’s we had both moved on but what she did next was just as remarkable and so much healthier for all involved. She set up the Mombasa Roadshow and I want to tell you about that next.

Postscript- 8/6/24. Today I received an email from a complete stranger. Her name is Christine Shirley and she has recently discovered this website and my story of Future Shock. She has written to me to tell me something she felt I should know about. I hope she doesn’t mind if I paraphrase what she has told me.

When John rang us all to tell us that the deal’s he had done with regard to the future of Future Shock [ Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, Tony Palmer film director, Granada TV, and an unnamed record company ] had all fallen through because of Alvin Toffler’s lawyers demands for extravagant percentages on any use of the name ‘Future Shock’, he was lying! He was offered a new deal that he never told us about. A deal that would have enabled all the interested parties to make a substantial profit from their involvement.

Christine’s father, Peter Shirley, had become aware of the appalling demands of Alvin Toffler’s lawyers and contacted Alvin Toffler to explain that, as a result, nobody could make any money with the extravagant percentages they were demanding and as a result, Future Shock, the stage show and all related deal’s, were off. The whole enterprise was ‘dead in the water’.

This new deal that her father [ now deceased ] put together with Alvin Toffler and his lawyers in New York, just needed John’s signature and everything would have burst back into life. But…when John met them, for reasons impossible to explain, he turned the new deal down. Apparently he [John] was very rude and just walked away from it. Christine still has a copy of this new deal, dated 15th May 1978. Her father had gone to considerable length’s, at his own expense, to negotiate this deal and was dumbstruck by John’s rudeness and ignorance. At this stage, he also walked away, disgusted. The deal never happened and all Johns dreams with it. Not to mention our dreams.

John was a complex character, brilliant at self promotion but also a control freak. I can only speculate as to why he destroyed his brilliant creation. Perhaps he just refused to allow anyone, other than himself, to profit from his ‘Baby’…but in doing so, he was completely naive about how big business works.

As I’ve related above, his attempts to go it alone with the Roundhouse fiasco, just proved that he didn’t know how to share responsibility to achieve the bigger picture. His ego was completely out of control and as a consequence…we all lost out.

I’m very grateful to Christine for sharing her insight into what happened but gutted to hear how things could and should have turned out. If only John had told us about this new deal, perhaps we might have been able to persuade him to loosen his grip on the steering wheel, for the greater good. He seems to have lost sight of the bigger picture…how sad.

When I rang Mary and told her about it, there was a pregnant pause on the phone and then she said “Just think about all the things you and I would never have done if we had become rich and famous…we’ve both had good and fruitful lives and who knows, perhaps better lives”. She’s so right! 8/7/24

THE MOMBASA ROAD SHOW

Nearly 4yrs passed before I met up with Mary again. A lot of water had flow’n under the bridge. Amongst other things, I had travelled to Australia and Indonesia, abandoning everything I owned here including a place to live. As the cliche goes, ‘wherever you try to run away to, don’t forget you take yourself with you’. I had tried to run away from a broken heart, politics and a loss of direction. Predictably, my travels didn’t resolve any of those things. When I returned, nothing had changed. Several good friends put me up as I tried to get a footing back in London. It was alway’s the place that had broken me and then put me back together again. I knew how to survive in London and in some way’s, it was also one of the loves of my life. It was the place that kept on giving.

By the late Spring/early Summer of 1982 I was still a bit rootless and then one day I decided to go and see Mary. It was so good to see her and she enthused me with tales of a theatre company she and some friends had set up called The Mombasa Roadshow. It was centered around Kingsgate Road NW6. I was still sofa surfing in South London and doing various jobs, including work as a park keeper in Dulwich Park, which I loved. There were bits and pieces of performance related work too. But there was something about The Mombasa Roadshow that caught my imagination and I wanted to be a part of it.

I’m going to try and write about this new experience but in a different way from the story of Future Shock. There’s no obvious arc to this story. This experience wasn’t about being cutting edge, it wasn’t about financial reward and it certainly wouldn’t cause pain to it’s participants. Quite the reverse. This would be about empowering people and giving them a sense of self worth and hopefully lifting them out of the trough of Margaret Thatchers depressing vision for Britain.

Let’s get the name out of the way first. I’ve just spoken to Mary and asked her a question that never seemed important to me before but it’s an obvious question to ask. Why ‘The Mombasa Roadshow’? Mary described how she was in Rosie’s cafe with Lester Haines and John Herlahey who, incidentally, she gives the credit to for actually coming up with idea for starting the company. [Both John and Lester are sadly no longer with us. They were very contrasting characters. Nobody I’ve spoken to has a bad word to say about John, who seems to have been universally loved. Lester was a far more complex man. A man of ideas and boundless energy but difficult to be around some of the time…a force to be reckoned with. I wish I’d got to know them better]. They were wondering what they should call the company that they were thinking of forming and were throwing ideas around. Mary had worked with Hull Truck Theatre Company, which is an unusual name for a theatre company and there was Ken Campbell’s Roadshow, which might have been an inspiration, but they didn’t want to assign any particular names of people or places to their company. One of the main things they wanted to establish was that it didn’t belong to anyone or anywhere. They should just choose something completely random, without meaning or identity. And one of them simply said, “How about The Mombasa Roadshow?” It seemed perfect, ok, it’s a place obviously but in North West London it wasn’t likely to carry any particular cultural meaning. And if it did, and someone rocked up hoping for something African, they might be initially disappointed but hopefully they would stay anyway and enjoy what was on offer regardless. On the one occasion when somebody did ‘rock up’ expecting a connection with Mombasa, it wasn’t to see theatre. I’ll tell you about that later.

That was in 1981. By the time I got involved in 1982, they’d already done a couple of shows and a format had been established. This was a company for anyone. Whoever rolled-up and wanted to be involved, could. There was a core group of participants but nobody was guaranteed a part, they were all up for grabs. If there was an aesthetic, it was Punk. Mary had said she was fed up with the way that theatre companies usually approached classical theatre and that she had met people down the laundrette who could bring more to the classics than professional’s did. Professional’s had fixed ideas about how such theatre should be spoken and performed. Mary and the others wanted to Punk it up. The main criteria being that they should stick to the classics… for the people, by the people. And so it was.

This wasn’t the first time that I’d encountered this approach and attitude to actors. Moira Kelly, who directed the production I was rehearsing in Eton Square [See The Lion of Eton Square story], had also voiced her doubts about trained actors and their inability to come fresh to the process. I had had to push my pride aside and eventually understood where she was coming from. If you approached this thing called ‘Theatre’ as an artist, then it was all about the creative process, not precedent.

Mary asked me if I would like to be involved. “You know more about acting than I do. You could help us. You could be a second pair of eyes on the things I’m not very good at”. I loved the idea of not acting, but helping others. I’d directed a children’s theatre production up in New Brighton about 9 years previously and had always wanted another go. I could still remember the buzz I got from doing it. I said “Yes, I’d love to help if I can”. The Mombasa’s were already rehearsing their next production, Ben Johnson’s ‘Bartholomew Fayre’, in St George’s Hall, Kingsgate Road [Later called Kingsgate Community Centre]. At their next rehearsal, I travelled up from Dulwich, met up with Mary and we walked up to the hall. I’m not sure what I was expecting but what greeted us as we walked in, was not something I’d ever experienced before. It felt like chaos. There were people having loud animated conversations, there were dog’s running rampant and young children too…and there was a strong wiff of cider. There were people on the stage doing theatre stuff…sort of, but the overwhelming feeling was one of anarchy. Mary asked everyone to gather round. Some did but others just ignored her. To those that did, she introduced me and said that I was there to help her with the acting and things like that. Some seemed ok with that but I also felt a bit of hostility from others. I stuck out like a sore thumb and I began to wonder what I’d let myself in for.

Earlier that year, after returning from Bali, I’d been to a Clash concert at the Colosseum. As I walked in, I was greeted with a sea of black leather and pale complexions. This was my first ‘sore thumb’ experience. I was still tanned and wearing a pair of yellow, sharks tooth print trousers, that I’d bought at Camden Lock about a year previously. In Australia they were much admired by the Sydney trendies. In fact, I had people offering to buy them off me. Back in the UK, in the intervening year, fashion had moved on…black was the new black, as the saying goes. And a pale complexion was de rigueur. This was Punk. I obviously hadn’t learned my lesson, as yet again, this time in West Hampstead, black was the predominant colour. I needed to adjust my uniform.

I was soon absorbed into the company however and I discovered that I wasn’t the only middle class emigre. There were people with considerable talents and intellects lurking in the ranks of the Mombasa’s and it wasn’t always obvious from their appearance or background who they were. This was to prove a very valuable life lesson for me and has stood me in good stead ever since. I would travel up whenever I could and give support to Mary and bit by bit, I became a Mombasa. It was, after all, a state of mind as much as a Theatre Company and I really started to enjoy just being with them. Somehow, I belonged and it felt like I had found a new home for my restless spirit. On May 18th, the show opened and I then discovered another reason for the uniqueness of the Mombasa’s…their audience.

When I arrived at the hall before the show, there was the usual hectic atmosphere but there was also a tension that I recognised from every theatre production I’d been involved with. First night nerves. Those of us that weren’t performing were kept busy going round and reassuring people that everything would be fine. Helping them with their costumes and make up. Unlike professional company’s however, there was a different set of values at play here. People who had never performed before were about to have their first experience of speaking publicly and not knowing if they had the balls to do it and withstand the public’s judgement. They all knew what was coming. I didn’t. Many of the company had been audience members at previous show’s and had been inspired to ‘give it a go’ and those that had performed before also knew what was coming and were simply girding their loins in anticipation. What was coming, was unlike any theatre show I’d ever seen.

For a start, there was no formal seating. As the audience started to arrive, the atmosphere was like the first time I’d encountered the Mombasa’s…chaotic and anarchic. They were loud and many were the worse for wear from cider and other substances and there were dog’s, again. It felt like they, the audience, were gearing themselves up for a performance themselves. In the same way the cast were but without having to learn any lines or wear costumes. It was more like the atmosphere before an illegal bare knuckle fist fight but without the gambling. Suddenly, I feared for the cast, but I shouldn’t have, they knew their audience and these were the people they had chosen to perform for. They were the audience and the audience was them. This was how the Mombasa’s differed from every theatre company I’d ever encountered before and the feeling was electric.

As the curtain rose, there were cheers and laughter and heckling. After all, these were their mates and they were got up in fancy costumes and were wearing make up. To some, they looked ridiculous. When a cast member made their entrance, they were often ridiculed and laughed at…but it was with affection and there was an underlying respect too. What balls it took to stand up in public and utter lines in ancient English, whether you understood them or not. There were arguments between those that wanted to hear these lines and those that didn’t give a toss. But as the play progressed, respect grew and people did listen. The hecklers were subdued…sometimes by other audience members but also from the cast themselves on occasion. There was direct eye contact between cast and audience. There was a meaningful dialogue taking place. As the poster for the play said, this show was: ‘Dedicated without permission to The Swine, The Rabble & The Wretches’. I’d never witnessed anything like it and it was wonderful to behold. Over the next few night’s, I could see the cast developing in confidence and something else became apparent too, the audience had become more diverse. Every night, the hall was packed but I began to notice people that I would have described as ‘Theatregoer’s’. This had a wide appeal and was being enjoyed by the whole community.

I should mention that, right from the word go, Mary had been in contact with West Hampstead Housing Association [WHHA]. In particular, Anna Bowman and Maireard Robinson [Google her Guardian Obituary], who had supported her from the outset and had helped her to secure St Georges Hall as a venue. They were both activist’s in the burgeoning Housing Association movement and it was thanks to them that so many of us had affordable places to live. I later benefited from their ‘Half Life’ initiative. It was the bridge between squatting and official Council Housing, whereby they would let out run down properties with running water and electricity at a tiny, nominal rent. Almost every ‘creative’ that I knew at the time, was living in these properties, thus making it possible for them to pursue their creative activities and survive on small incomes. It became the bedrock of the creative arts.

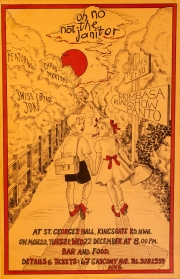

As the summer progressed, I was still living in South London and surviving on a mix of park keeping, driving and some small arts projects. In September, I heard that there was a spare room at 47 Gascony Avenue NW6. It was just round the corner from Kingsgate Road and was where some of the core members of The Mombasa Roadshow lived. Allan, Helen and Nicky lived there and had offered me a room in their shared house. I moved in immediately. It turned out to be an opportune moment to be there as the Mombasa’s were about to embark on a new project and this time it was going to be a Panto. They hadn’t done a Panto before and it required something that none of us had ever done before…writing.

I had managed to get a job, driving for a company called Taxivans, who were located on Finchley Road. It was gruelling work but quite well paid. One of it’s main advantages was that they were happy to let me pursue other projects when they cropped up. It was perfect and fitted all my requirements at the time. After a hard days work, I would return to Gascony Ave. where the household would get around the table in the evenings and start to thrash out ideas for this Panto. We needed an idea to hang the whole project around and at some point someone suggested the image of the ‘Start Right Kid’s’ from the advert used by the shoe company in the 1950’s/60’s. It was reminiscent of ‘The Yellow Brick Road’ in ‘The Wizard of Oz’, with two young innocents walking, they knew not where, into a new future. Suddenly we knew where this was heading. In contemporary terms, we saw it as two young school leavers, heading off to the Benefits Office, where they would encounter the Ogre of the Benefits system. Perfect. We had our villain and an impossible dream. We had the bare bones of the traditional Panto setting but with a distinctly Mombasa twist. We were on our way.

One night, as we struggled to write by committee, there was a knock at the door. Outside stood a Chinese man. He was rather confused and seemed lost. Whoever answered the door, asked him in as it wasn’t quite clear what he wanted. He was reluctant to come in at first. He said he was hoping for some connection with Mombasa in Kenya, but must have realised immediately that that wasn’t what this household represented and was therefor unsure how or what to say. As he came into the room where we were writing, we were as baffled by him as he was by us. We welcomed him and invited him join us at the table. Somebody thought a drink might be in order and so a bottle of whiskey was produced. He declined the offer of a drink but we started to tuck into it anyway. The occasion seemed to call for it. He explained to us in halting English that he had seen one of our posters and it had our address on it and he had somehow found his way to the house. He had assumed that we were in some way connected to Mombasa. As that obviously wasn’t the case, he didn’t quite know what the rules of engagement were. He was culturally completely at sea. We sensed fear and confusion and tried to reassure him that it was ok and that he was safe with us and that we would like to help him if we could. In his desperation, he seemed to decide that he was just going to have to take a leap of faith and trust us. He started by telling us that he was in the Chinese Diplomatic Service and was based at the Chinese Legation in Mombasa. He had never been to the UK before and had arrived here earlier that same day. He was looking for someone. His daughter. She was studying in London and had contacted her family in Mombasa and told them that she had decided that she wasn’t going to return there because she was having a relationship with a woman she had met. She was in love with this woman and knew that this would bring shame to her family because homosexuality was illegal in China. He had come to take her home before anyone found out. He was terrified. It wasn’t just shame he was worried about. He was worried for his life. He was literally shaking.

10 minutes earlier, we had been sitting around trying to decide how to write the script for a Pantomime and now, here we were, with a complete stranger from a very different culture, presenting us with a profound and heart wrenching problem. As we took all this in, we realised what a dreadful predicament he was in and struggled to know how to respond. Our first response was to try to explain to him that, in English law, he couldn’t just whisk her away unless she was willing. I think we all felt a bit responsible for this poor man’s situation. After all, in calling the company The Mombasa Roadshow, we had inadvertently brought him to our door, but how could we possibly help or advise him? This felt like an enormous responsibility and we needed to be very careful with what we said. An intense conversation between ourselves followed as he looked on. We couldn’t involve the Police. We didn’t know anyone who knew about International Law. We couldn’t even agree on what we thought about his response, driven by Chinese Communist doctrine versus our Liberal Democratic ideology. Should we be protecting his daughters rights under our laws or responding to his very real concerns for his and his families fears of retribution by the Chinese authorities? These were issues way beyond our capabilities. In the end, we decided that the only way we might be able to help both parties, was to try and bring him and his daughter together somehow. Only they could resolve this. He then admitted to us that he had been to the house where his daughter was living and that they had refused him entry or contact with her. All we could do was to try and find an intermediary that could break this impasse. We suggested that he speak to someone at West Hampstead Housing Association the next day and that one of the women there might be prepared to try and act as a go between. We couldn’t think of any other solution. He shook his head. He couldn’t understand the concept of asking a feminist to speak on his behalf. He decided to go. He thanked us for listening to him and left. Disappearing back into the night.

We have no idea what happened next. We will never know. I can’t forget that night. In retrospect, I can see that in some strange way, the events of that night fed into the Panto. It was the juxtaposition of the profound and the ordinary. The complete randomness of the events of that night and the fact that it just left you wondering “What next”?

And so we continued to try and write this show. We had a starting point and a rough thread with the young kids weaving their way through the byzantine benefits system. In many ways we were starting to have too many ideas but how could we tie them all together. I saw this as a positive. Why not retain all these random elements and non-sequiturs? I was a big fan of ‘The Theatre of the Absurd’ and this felt like something we should be embracing. We had some traditional elements of Panto, like The Ogre and a Good Fairy and we even had a Jack and the Beanstalk sketch, but instead of a beanstalk, it was a cannabis plant and Jack would return as high as a kite. But we wanted it to be so much more. I thought we should bring as many of these random elements into the show as possible and that the cast should acknowledge when they were confused by looking directly at the audience and shrugging their shoulders, as if to say, no, we don’t understand what’s happening either. It might help to draw the audience in. I then suggested that we could introduce a further random element by having a Janitor who would appear amongst the audience from time to time and demand to see tickets and complain about the fact that no one had told him there was going to be a Panto in the hall that night. He could go round sweeping up any litter he saw and getting people out of their seats as he did so. Just being very disruptive. The cast could then come out of character during these interruptions and declare “Oh No Not The Janitor” and encourage the audience to join in. It would be our equivalent of the traditional Panto cry of “He’s behind you”, “Oh no he’s not”, “Oh yes he is” thing. Nobody volunteered to play this part, so it fell to me to be the Janitor. At least that way, if it didn’t work, I only had myself to blame. And of course, we now had a title for the show.

This was beginning to feel like the sort of Panto that the Mombasa’s should be doing. Out there. A complete de-construction of the norm. Risky and edgy. But would our audience go along with it? Could we pull it off? It would require complete conviction from the cast…except where we’d built in a knowing complete lack of conviction of course. Confused? We certainly were. But that was the whole point. Disorientation was the name of the game. I recently discovered that I had a copy of the script and I re-read it. It makes no sense at all. On paper it’s dreadful. As Geoff Sample say’s on his website [Google Mombasa Roadshow and Geoff Sample]…you had to be there.

On the night of our dress rehearsal, things didn’t feel that good. This was a show that would only work if the audience bought into it and became participants in it. It felt like a massive gamble…but I believed in it and stood by the decisions we had made. I went back to my flat with a slight sense of trepidation and hoped against hope that we hadn’t pushed things too far. I’d wanted to get home that evening because the BBC was showing a new comedy series that had been billed as ‘very new’. I was intrigued. It was called ‘The Young Ones’…and the rest is history. It was amazing. It could so easily have been ‘Oh No Not The Janitor’. It had the same non-sequiturs and surreal elements to it. It had bad acting and unlikely alliances. It was anarchic. It was our Panto… televised. And on the BBC. We had unknowingly hit the zeitgeist.

Our audience loved it. And so, after a few nights, it slipped away into the annals of history, unnoticed. Unlike ‘The Young Ones’, which was lauded as the future of comedy, like ‘The Goon Show’ and ‘Monty Python’ before them. A friend of mine recently asked me if I wasn’t a little bit peeved at seeing the success of ‘The Young Ones’? To which I replied that yes, there was a bit of me that thought we deserved some recognition for what we had done. But I was equally proud of the fact that we had come up with something so groundbreaking and that, as with all the Mombasa show’s, we had given our extraordinary followers something of real quality to chew on. We were The Mombasa’s and we went where others feared to tread!

As a postscript, I would just like to add that ‘Chris Morton’s Swiss Cottage Joke’, as immortalised on the poster [not requested and a complete surprise when I saw it], was not that funny really but arose out of the fact that one of the cast, French Julie, had trouble pronouncing the word Scottish, she pronounced it as Scottage, to which I, as the Janitor, responded “Oh, you mean like Sviss S’Cottage”. I told you, not that funny, but it seemed to stick in peoples minds and I couldn’t feel prouder when I see the poster.

After the Panto I went off to do other things and the Mombasa’s had a pause in their activities, but in 1989 they re-emerged to do ‘The White Devil’. By this time Thatchers revolution had meant that our old venue had been taken over as a Community Centre and like all things Thatcherite, it was no longer available to us free of charge. The days of doing theatre on a shoestring were a thing of the past but somehow Mary had managed to get a slot at the wonderful Diorama in Regents Park. My involvement was minimal but I enjoyed meeting up with the Mombasa’s for one last time. Mary was at the helm and I did my thing of helping the cast with their performances and just enjoying being with them again. They did one more show at the Diorama [The Bacchae], in 1990 and as far as I’m aware that was it. All good things come to an end it seems and for the Mombasa’s that was it. In a recent conversation with Mary, I tried to encourage her to write the definitive story of The Mombasa Roadshow. I’ve only scratched the surface with my tale of being with them. I hope she does it because it’s an amazing story and deserves to be fully documented. If you’d like to see some great backstage photo’s, I recommend going to Geoff Samples website as mentioned above. Just Google Mombasa Roadshow and you’ll see his site at the top of the search list. I should thank Geoff for helping me to re-engage with Mary, Helen and Allan after 30yrs and for the exchanges I’ve had with them as a result.

At the enormous risk of missing someone out, I just want to mention the wonderful people that constituted The Mombasa Roadshow during the only too brief time I spent with them:- Mary, Lester, John, Allan, Helen, Nicky, Mandy, Geoff, Drew, Felix, Jane, Sue, Dog, Donald, Martyn, Paul, French Julie and Neil [who is still one of my closest friends and who played the humble part of ‘Tree’ in the Panto and has never forgotten it]. My gratitude to you all for accepting me into your ranks. I hope this re-telling does you all justice. If anyone reads this and can add more names [and I know there are more names ] please email me via the email address at the top of each page by clicking on it and I will gladly add them to the list. I will always be proud to call myself a ‘Mombanista’!